The perfect obituary for a photographer

My wife sings in the funeral choir of our church where all too often she learns about other people’s lives and family too late to enjoy the living.

The eulogies are always gracious with friends and family speaking about the transitional moments in relationships, how their lives were changed by the relationship, and how sorrow becomes the catalyst that brings them all together to remember another’s life.

That was the situation several years ago when my mother-in-law died after battling heart problems. Her family gathered in the crisp cold of a North Dakota winter.

“Family had gathered to celebrate the gentleness of a woman whose tumultuous life never betrayed her love for her children. We stood together, in tears, not afraid to speak of the good things, the moments of congratulations and celebration bequeathed to her children. A gift to pass along to the following generations without condition or regret.

“Early winter’s fresh snow near the rock changed the landscape ever so briefly reminding me of that moment, when brothers and sisters, aunt, uncles, nieces and nephews gathered in a place to celebrate a life. We were in that moment of cold between death and resurrection when only memories brighten the day and tears wash away the sadness. It’s a shame it sometimes takes the bitterness of death for us to celebrate the good in people’s lives.” – From The Rock At Inniswood.

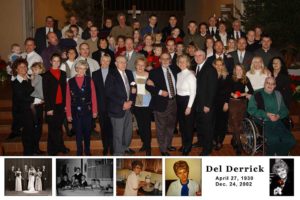

Several weeks ago one of the daughters mentioned on Facebook that it was the anniversary of her death and how much she was missed. Minutes later I’d uploaded a photo of the family gathered at the church after her funeral. Everyone stood close together, joined in grief and joy.

Several years ago the New York Times wrote about the elevation of obituary writers to lofty news writing icons. The task once detailed to the lowest of copy writers is now a much sought after job where style is measured beyond the ability to lace a linear timeline into a cohesive description of life passed.

My mother never trusted obituary writers, even the ones who wrote the succinct one-column catalogs only published in her local paper accompanied with a photo of an undetermined date to best illustrate the best day in their life.

She didn’t want her life’s catalog to omit anyone, any important event, and any family connection no matter the status. To make sure, she wrote her own obituary.

It’s difficult to say but she was fortunate that she knew death was coming. She’d survived an earlier fight against cancer but knew her second battle aggravated by a heart problem would not be one she’d win. She wasn’t eager to die but believed she’d soon be with my dad and that was all that mattered at the end.

Her obituary was perfect, completing a life of honor and dedication to family and friends.

During the discussion about obituaries with my wife she asked if, like my mother, I would write my own to make sure it was accurate and inclusive of all that mattered to me.

“My photography is my obituary,” was my answer.

The collection of all the 1/125th of a second frames, of all the spot news, sports, features, portraits, landscapes, and snapshots, would speak for me at my death. I’ve no idea how many photographs I’ve taken. Nor how many times I’ve pressed the shutter, watched as the screen went dark and then returned to brightness revealing the moment after the photo I didn’t see.

I’ll never know how many people have seen my photography. After more than 40 years shooting for newspapers and The AP there would be no way to know.

I do know about the lady behind my wife at the grocery store in Ft. Lauderdale who talked with another customer about my photos that were in the previous day’s newspaper.

I do know about the father who greeted me with his phone showing off the photos I’d taken of his son and hearing about how he will never delete them.

There are more stories than I can ever remember of people telling me about a photo I’d shot of them or a photo they saw published that they affected them.

Got that response from mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, police officer and firefighters, a president, several governors and many politicians, kids, criminals, and death row inmates.

The common thread for all of them was my photography. It spoke to them and was now registered in their memory. At the lower corner was the credit line “Photo by Gary Gardiner.”

One of the plans for my funeral is to continue My Final Photo until the cold earth is lowered over the casket.

I’ve arranged with friends to set up a camera in my casket as if I’d just pulled it from my eye so they can see my final pose. As each passes the casket the camera will shoot a frame and deliver it to the My Final Photo Web site. My obituary, at least my obituary of photos, will continue after my traditional obituary is printed in the local paper.

Every day, as I prepare myself for the task of creating another photo for the My Final Photo project, I want to be sure, if it is indeed my last photo, that it is memorable. That it is storytelling and evocative. That it contributes to the story of my life in some way that others might be interested in vying to be the writer and photo editor for the New York Times who will tell my story.

My son-in-law says my tombstone should read:

Her Lies Gary Gardiner – Photographer

“Pretend I’m Not Here”

That may be the perfect obituary for a photographer.